Raw material prices are hovering near a six-year high as automakers wrestle with volatile costs of steel, aluminum, copper and plastics.

In August, raw material costs for North American-built vehicles averaged $2,000 a unit — about $221 more than a year earlier — according to the New York consulting firm AlixPartners.

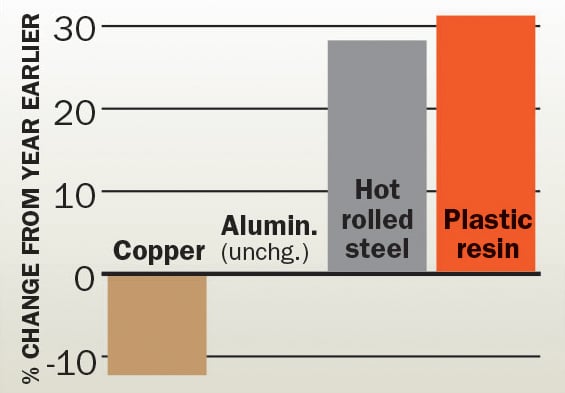

Four commodities account for the bulk of a vehicle's raw material cost: steel, aluminum, plastic resin and copper. The price of copper and some other materials "have started to come down from their peak in May and June," said Dan Hearsch, a managing director of AlixPartners.

But there's a catch. U.S. manufacturers must pay a 10 percent tariff on imported aluminum, so the price of that metal could prove volatile. And the AlixPartners index — which derives aluminum prices from the London Metal Exchange — does not yet reflect the tariff.

In June, the White House subjected Canada and Mexico to U.S. aluminum and steel tariffs. Automakers are starting to feel the impact.

In September, Ford CEO Jim Hackett acknowledged that the tariffs cost his company $1 billion in profits. And in July, General Motors said second-quarter commodity costs were $300 million higher than a year earlier.

Hot-rolled steel prices have jumped 28 percent to 40 cents per pound over the past year, according to AlixPartners. Automakers buy most of their steel in North America, but certain types — such as stainless and electrical steel — are imports subject to the 25 percent U.S. tariff.

Meanwhile, plastic resin prices rose 31 percent as feedstock costs jumped over the past year.

To control commodity prices, automakers typically buy in bulk for resale to suppliers. Toyota Motor Corp. does so for steel, aluminum and plastic resin, says Bob Young, the automaker's North American purchasing chief.

Toyota also allows suppliers' component prices to float up or down as raw material costs fluctuate.

"We believe our suppliers can't control commodity prices," Young said. "We don't want our suppliers expending resources trying to manage that. We want them to focus on costs they can control."

Suppliers are expected to minimize scrappage and cut weight.

"If the supplier has 50 percent scrappage, that's not a cost that we will absorb," Young said. "If they are not efficient, they will absorb the cost."

The big-ticket commodity is steel, Young says. In North America, Toyota's steel purchases total $1.8 billion a year. Toyota negotiates one-year steel contracts that are renewable in April, so the company has been somewhat insulated from recent price increases. But only somewhat.

Young says steel prices in North America are significantly higher than in other regions.

"If you look at different types of steel — hot-rolled, cold-rolled, coated — it's roughly a 40 percent gap," Young said. "That's hard to justify from a cost standpoint. If we want to remain globally competitive, we need to see an improvement in pricing."

So what does the future hold for raw materials? Hearsch is reluctant to make predictions. In the first eight months of 2018, North American light-vehicle production totaled 11.4 million units, down from 11.8 million a year earlier.

Theoretically, raw material prices should ease as demand slumps. But it's unclear whether vehicle production accurately forecasts a wider economic downturn, Hearsch said.

"The auto industry is just one of the big users of these raw materials," he said. "Production is slowing, but we're not predicting whether this is a big downturn."